Who's Afraid of Quiet Luxury?

What makes something nondescript so compelling? And why do some people hate it so much?

Note: While I get the hang of this newsletter thing, I will occasionally be publishing stories I have written previously that have not appeared online. This essay was originally published in issue 14 of Mastermind Magazine.

King Charles III, monarch of the United Kingdom and Head of the Commonwealth, has worn the same shoes for 50 years. A pair of gleaming mahogany leather brogues have served as the King’s loyal subject since 1971, sent away to a cobbler for repairs any time an errant Royal toe threatens to poke out of the sole. He does the same with suits, making frequent public appearances in visibly frayed jacket cuffs that have been mended many times over. One jacket in particular, he has admitted to owning since 1969. Perhaps he picked up this peculiar habit from his father, Prince Philip, who purchased a new pair of shoes for his 1947 wedding to his third cousin, Queen Elizabeth II, and proceeded to wear them for the next 74 years straight.

The King of England is worth an estimated $2.3 billion. He undoubtedly has access to any number of bespoke shoemakers across Britain. His daughter-in-law, Kate Middleton, is rarely seen wearing the same outfit twice. So why does the King consistently wear the same clothing over and over again?

It all boils down to a buzzword igniting the fashion world since the beginning of 2023: quiet luxury, or as it’s sometimes called, stealth wealth. Quiet luxury typically refers to a minimalist, understated way of dressing favored by the fabulously wealthy.

It’s the Hermes scarf casually tied around Jackie O.’s head to preserve an expensive blowout. It’s Steve Jobs’ closet full of identical Issey Miyake turtlenecks. It’s even Bernie Madoff’s predilection for monogrammed Charvet dress shirts. On first glance, the items in question might seem relatively simplistic; virtually indistinguishable from the offerings at Uniqlo or Muji. But what sets them apart is their superior fabric and painstaking construction – fine details that come at an eye-watering price.

Quiet luxury has risen to prominence thanks to a number of commingling factors: the popularity of the TV show Succession, depicting the adult children of a billionaire, oft clad in loose khakis and Moncler puffers, locked in a power struggle for control of his company; the TikTok revival of Ivy League style characterized by pleated tennis skirts and rugby shirts, and perhaps a general fatigue of cloying eccentricity as the dominant aesthetic, exemplified by the cacophonous clashing of Alessandro Michele’s Gucci. (He departed his role as creative director of the brand in November 2022.)

Seasons marked by sameness prompt the eyes to hunger for something different, and suddenly, the cleanliness of a crisp, oxford button-down paired with billowing silk trousers becomes a balm for the senses. Plain leather loafers with no distinctive qualities at all abruptly become preferable to the umpteen variations of bloated statement sneakers on the market. Quiet luxury is mature, the antithesis of the racing TikTok trend cycle that champions nonsense aesthetics like “mermaidcore,” “blokettecore,” and “okokok vs lalala.”

Quiet luxury is compelling specifically because it is nondescript. It’s not immediately clear what makes it special, so we go searching for answers in the blandness of perfectly pleated khakis, cashmere cardigans and passed-down strings of pearls.

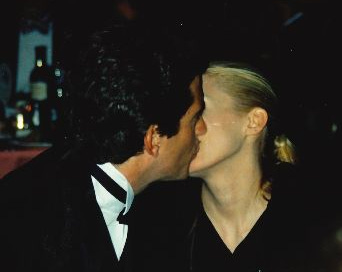

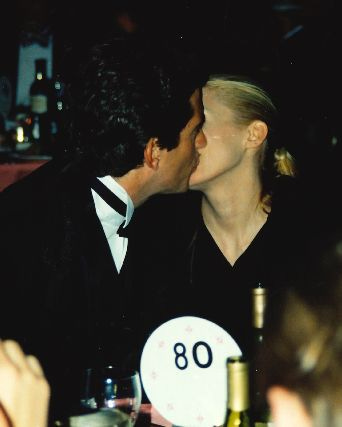

Take Carolyn Bessette Kennedy for instance; one of the most compelling style icons of the 20th century who remains enshrined in memory for wearing clothing so spartan it was practically austere. Her wedding dress was an undecorated white slip (designed by Narcisco Rodriguez), a white button down oxford paired with a sleek black maxi skirt was considered formal dress. Often clad in an unadorned wool pea coat and jeans for a jaunt around the city, the media scrambled for ways to explain her appeal, coining terms like “throwaway chic” and “effortful effortless.” What they’re grasping at straws to describe is the luminous quality that comes from wearing sparse items with confidence. Normally we tend to associate a command of style with the ability to mix and match items with eye-catching flair. But Bessette’s mastery of simplicity and her ability to inadvertently draw attention wearing clothes that were outwardly unremarkable is a feat of quiet luxury. As the adage goes: money talks but wealth whispers.

But to treat quiet luxury as a purely aesthetic phenomenon is to misrepresent the attitude central to its existence. Stealth wealth is not a series of visual signifiers but the nonchalance with which dressing is approached. It’s a philosophy of dressing that values high quality items worn consistently throughout time – something any article purporting to offer ‘the quiet luxury look for less’ cannot account for.

As King Charles quipped, “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible…and in this way I tend to be in fashion once every 25 years.” Quiet luxury doesn’t have to mean polo shirts and sweater sets or head-to-toe The Row; it can be an art gallerist’s collection of high-concept Comme des Garcons or the haute maximalism of TikTok star Carla Rockmore. As people age, they tend to settle into fixed identities and begin to dress accordingly. As Bianca Salonga writes in Forbes, “A wardrobe of quiet luxury items considers the real life needs, inclinations, and movement of the wearer.”

However, many critics have chafed at the term, accusing it of snobbery and elitism. It goes without saying that the brands inhabiting the quiet luxury universe, like The Row, Khaite, Bruno Cucinelli, and Loro Piana are exorbitantly expensive. In a story for The Cut titled ‘Quiet Luxury is Actually Very Loud,” author Tiana Randall suggests the “elitism of this obsession just entrenches existing economic inequalities.” But if the definition of quiet luxury is “high-quality materials, craftsmanship, and heritage,” as stated earlier in the piece, it doesn’t seem like such a bad thing after all. Hermès Birkins, sewn from start to finish by a single artisan who has trained for a minimum of five years to be worthy of the task, aren’t elitist simply because they exist; they’re elitist because widespread income inequality makes them inaccessible to the masses. If anything, the world could use a greater emphasis on craftsmanship. Luxury deserves to be democratized so more people can enjoy it, as opposed to done away with altogether.

While precious few have a spare $2,000 to drop on a single Khaite cashmere cardigan, many people fail to realize that ‘high quality’ and ‘inexpensive’ are not mutually exclusive categories. Seasoned secondhand shoppers will know that TheRealReal is crammed with $30 Prada pumps and Max Mara pencil skirts for as little as $10 if you have the sense to ‘sort low to high.’ Designer clothing is not expensive if you know where to look. A wardrobe filled with high quality things that will last is a hallmark of quiet luxury. Sustainability educator (and former Esprit designer) Lynda Grose, who taught fashion at California College of the Arts for many years, suggests that consumers view designer clothing as less disposable because they’re considered investment pieces. Basically, if you have to save up in order to buy something, you’re more inclined to treat it well.

Ultimately, quiet luxury has captured the collective imagination to such a degree because it's poised as unattainable – but in fact is not at all. The 1 percent aren’t dressing according to secret codes that anyone below their income bracket can’t pick up on and there’s no special way to tie a sweater around your waist that will get you an invite onto a billionaire's yacht. In the absence of these things, all that remains is a sense of ease that comes from being comfortable in one’s own skin (and yes, more than enough money to buy whatever they need). To achieve the unbotheredness that quiet luxury portrays, it’s crucial to stop chasing trends full stop. After all, the real luxury is knowing one’s own taste.