That Time I Met Patti Smith

On the iconic musician's sense of style, plus what it was like to interview the living legend.

This essay was originally published in issue 09 of Mastermind Magazine.

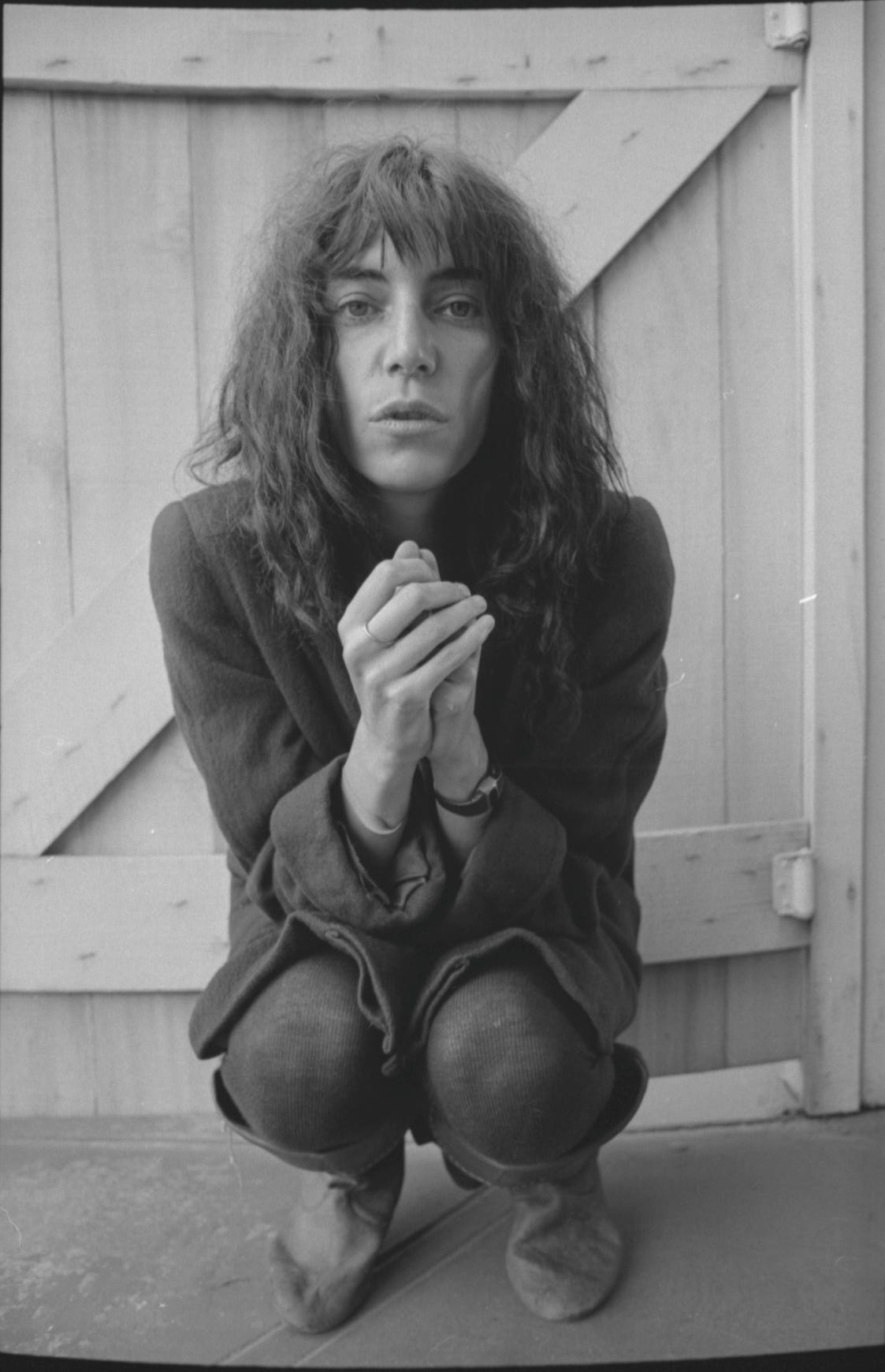

When I met Patti Smith in the lobby of the Le Germain hotel on October 13th, 2015, she was wearing a boxy suit jacket, worn-in leather boots and a faded pair of slack-fitting jeans rolled up to the ankles. Her long grey hair was fashioned into a skinny braid, nearsighted eyes hidden behind black plastic frames and a wisp of moustache dusted her upper lip. The elder statesman of punk rock had arrived in Toronto to promote her latest book, M Train, a follow-up to Just Kids, the ode to the bohemian paradise New York of her youth. I was a rookie reporter sent there to unravel her animus for a Canadian national newspaper. Though I had long been a fan of Smith’s music -- the delirious, frenzied pace of Horses was the veritable soundtrack to my teenage ennui -- I was completely struck by the deliberateness of her self-presentation. Smith’s outfit was plain, even inconspicuous, each garment clearly chosen for its superior cut and durability. Yet like an alchemist, her mere presence ensorcelled the outfit into something greater than the sum of its parts. On Smith, the quotidian became the devotional.

As a punk rocker, Smith’s brash poetic verses set against discordant guitars opened the floodgates for a new musical movement, but in her six decades of fame she’s become equally revered for her sense of style as she has for her art. The self-described “skinny loser” has inspired countless fashion editorials and ad campaigns, from Paul Smith to Balenciaga to Ann Demeulemeester. But to unravel what exactly makes her unbrushed hair, no makeup, and secondhand clothes hanging off her lanky frame so compelling proves more elusive.

Most style icons can be explained in three adjectives or less, but Smith is a shapeshifter whose endlessly mutable essence seems to slip through one’s fingers. Her penchant for oxford shirts and suit jackets is often unfairly characterized as “menswear-inspired,” a descriptor that reduces her wild, coltish energy to a rote appreciation for men’s clothes. But Smith is less a girl playing dress up in boy’s clothes, than something else entirely. Smith exists beyond the spectrum of gender; instead of being caught between two poles, she exists independent of the spectrum entirely. Her gender is that of Dickensian orphan, ragamuffin, Arthur Rimbaud wearing an off-kilter cravat.

Her gender is that of Dickensian orphan, ragamuffin, Arthur Rimbaud wearing an off-kilter cravat.

According to an anecdote recounted in her memoir Just Kids, Smith began to chafe against the tight strictures of gender early in life. After being scolded by her mother for refusing to put on a shirt, Smith resisted her mother’s instruction that she was to grow into a young lady. Smith never wanted to be a girl or grow up. Instead she considered herself a member of Peter Pan’s tribe of Lost Boys, a sort of genderless fairy who claimed adventure and imagination over any sort of adherence to tradition. In our interview, Smith recalled, “I always felt alienated as a kid. I completely knew what it tasted like to be outside society. I grew up in the ’50s and all my girlfriends had beehives, while I had greasy braids and was reading books all the time. I wished I was in a different time, like 19th-century France or something.”

It’s precisely this alien quality that makes Smith so compelling. While her peers were preoccupied by either the hyper capitalist tome The Money Game or its countercultural counterpart The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Smith found Hosanna in the work of William Blake and Picasso. Just as her cultural tastes are uniquely forged and a little out of step, so too is her sense of style. Smith wears clothes with a certain deliberateness, treasuring every possession as if it were a diamond sifted from gravel.

In Just Kids, she describes digging through thrift stories in the Bowery for “tattered silk dresses, frayed cashmere overcoats and used motorcycle jackets.” Other times, she searched for “just the right black turtleneck, the perfect white kid gloves.” In the 1960s and ‘70s, her lack of discretionary income precipitated a highly intentional approach to dressing that remains with her to this day.

Smith’s style is less a repudiation of gender roles than it is an embrace of playing adult dress-up. On infiltrating the highly selective social scene at Max’s Kansas City, Smith writes, “I approached dressing like an extra preparing for a shot in a French New Wave film. I had a few looks, such as a striped boatneck shirt and a red throat scarf like Yves Montand in Wages of Fear, a Left Bank beat look with green tights and red ballet slippers, or my take on Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face, with her long black sweater, black tights, white socks and black Capezios. Whatever the scenario, I usually needed about ten minutes to get ready.” Smith arrived at her identity through collage: by appropriating military clothes, men’s garments, and Keith Richards’ hairstyle, she was able to initiate a look that was entirely her own.

In his 33 ⅓ book on Horses, author Philip Shaw writes, “I take pleasure not just in the visceral drives of Patti Smith’s music, but also in her ability to tease out thought, to place the body and the mind in exquisite tension.” Smith is defined by this intense duality, embodying the opposing poses of light and dark, male and female, accidental and intentional. By virtue of being many things at once, she becomes herself.

As her star ascended, so too did her style. In Dream of Life, a 2008 documentary about Smith directed by her friend Steven Sebring, Smith points at her shoes, pants and shirt, reciting, “Prada, Prada, Comme Des Garçons….’ Designer Ann Demeulemeester cites Smith’s iconic laissez-faire as the inspiration for her entire career and the two have forged a lasting friendship based on a mutual obsession with the practical over the precious. To Smith, clothes are meant to be worn, not possessed, and she approaches dressing as a practical activity rather than a mystical one. “I’ve always looked the same,” she once stated in an interview.” “As a kid, I had a sailor shirt and the same old corduroy pants, and that’s what I wanted to wear every day”; a habit that has continued even as her means have grown. Demeulemeester describes her compatriot thusly: “She is very aware of her style and she controls it. It’s about being conscious of who you are and using all the strength you have to communicate that.”

Throughout the course of our 30-minute interview, which seemed to stretch on forever, I became even more enraptured with the Patti Smith that exists beyond her music. I was taken by her radiating sense of inner calm and her ability to consume copious amounts of herbal tea. She was generous with her time, showing me a text message containing a selfie from her daughter and complimenting my shoes. (Spanish patent-leather oxfords with a small block heel, for the record.)

She wrote down her personal email in my notebook and urged me to contact her in case I had any follow-up questions. Minutes later, I swiftly exited the hotel, rushing home to make sure I had caught every word on tape. I tucked away the notebook and never reached out, not wanting to invade the precious privacy of a living legend. Something about meeting Smith had ignited a desire in me to preserve the mystery of her existence instead of attempting to decipher it. Sometimes it’s far more powerful when a little bit of the enigma remains.

What a beautiful piece of writing, both about her and her style.